In the few months remaining before the UN Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, governments, business leaders and financiers at the frontline of climate action will have a new, critical study to ponder. The first instalment of the The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC AR6)has just been published. Called Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, the report has a stronger, clearer and more confident tone about climate change effects and the direction to take.

195 member governments from the IPCC approved the report, through a virtual session that was held over two weeks. It is a call for politicians, civil servants and business leaders to leverage the advances in climate science and technology that we have achieved over the years to improve climate negotiations and decision-making.

The report details the scientific community’s research on the current state of the climate. It reviews the changes observed in the climate system, the role of human influence, possible future scenarios based on forecasted levels of greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, climate information relevant to various regions, as well as how we can limit human-induced climate change.

Here, The Recursive presents and reflects on a few highlights of the new IPCC report, especially in connection to the effects of climate change in Southeast Europe.

Our planet is warming at unprecedented pace in the last thousands of years

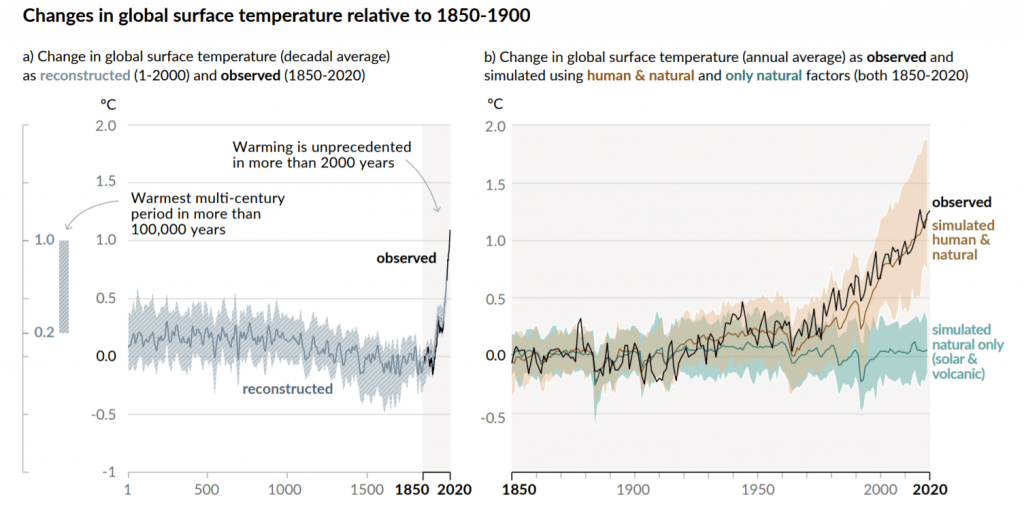

The new IPCC report comes with an improved assessment of historical global warming increases based on observational datasets.

Global temperatures have increased successively in every of the last four decades and at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2000 years. Human-induced GHG are responsible for approximately 1.1°C of global temperatures increase since 1850-1900.

Averaged over the next 20 years, global temperature is expected to reach or exceed 1.5°C of warming. Unless immediate, large-scale reductions in GHG emissions happen, it will become impossible to limit warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C.

“Stabilizing the climate will require strong, rapid, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, and reaching net zero CO2 emissions,” said Working Group I Co-Chair Panmao Zhai. In addition, limiting other GHG emissions and air pollutants, particularly methane, will also benefit the climate and our health.

Humans have an undisputed influence on climate change

Not only has it been clear for decades already that the planet’s climate is changing, but the influence of humans on the climate system is undisputed, says Dr Valerie Masson-Delmotte, Co-Chair of Working Group I.

Human influence has warmed the atmosphere, land, and ocean. As a consequence, widespread and rapid changes have occurred in the atmosphere and on the surface of the Earth – the oceans, cryosphere and biosphere. Evidence shows that greenhouse gases (GHG) and air pollutants, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), are driving climate change. And human activities have been partly responsible for increases in GHG concentrations since around 1750.

With the new report, scientists also shared a better understanding of the role of human-induced climate change in intensifying climate and weather events, such as heavy rainfall, heat waves, and ocean warming.

Importantly, humans still have the potential to change the course of climate – mitigating changes and limiting their effects.

Climate change effects are present in every inhabited region on the globe, including Southeast Europe

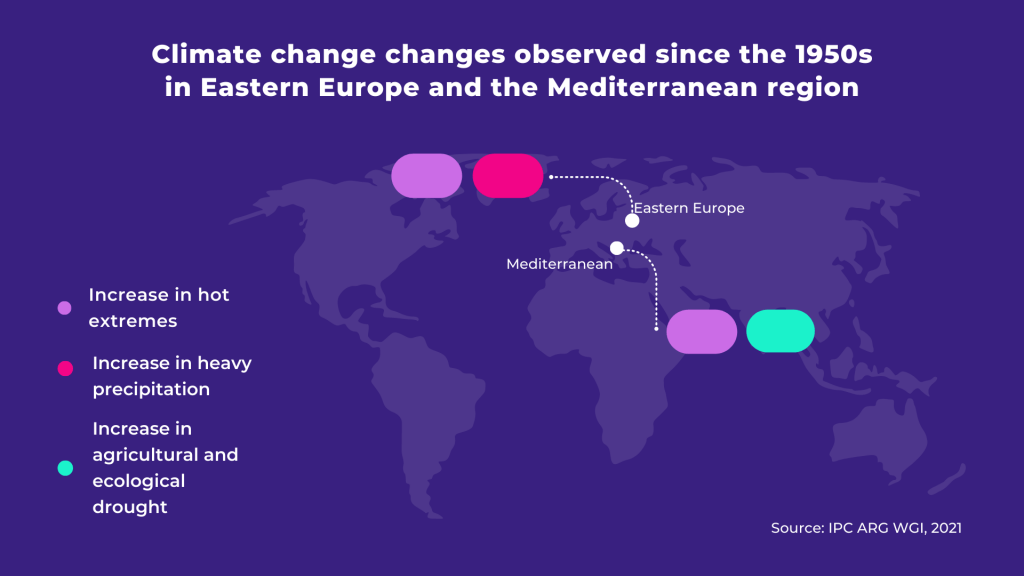

Since the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, scientists have also made progress in understanding the response of the climate system to human-induced GHG emissions. Thus, we have stronger observations of changes in extreme weather events such as heavy precipitation (rains, storms), heatwaves, and droughts and their attribution to human influence.

For instance, hot extremes, including heatwaves, have increased in frequency and intensity around the world since around 1950, while cold extremes have seen the opposite effect. Scientists can say with high confidence that human-induced climate change is the main trigger of these changes.

Likewise, the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have grown during the same time, with human-induced climate change likely the main driver. Meanwhile, land water evaporation and transpiration has led to increases in agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions.

Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean regions also experience various changes in climate and weather extremes. Both regions are seeing an increase in hot weather extremes since the 1950s, much like the rest of the world. Moreover, Eastern Europe, alongside Northern and Western Europe and most of Asia is experiencing heavy precipitation events. Scientists also agree on an increase in agricultural and ecological drought in the Mediterranean region.

There is no doubt that the agricultural sector, on which many of the Western Balkan countries are dependent, is under increasing pressure from extreme weather and climate events. High temperatures, drought, flooding caused by heavy precipitation, hail and windstorm – all can significantly reduce production potential. Furthermore, losses in production can substantially set back the economic development of these countries and can drive vulnerable communities into poverty loops.

What increases the impact on agriculture even further is that unlike any other human activities, agriculture is both a victim and also a cause of climate change. Around 18.4% of global GHG emissions come from agriculture, forestry and land use, rendering measures that decarbonise and increase the sustainability of agricultural practices as critical. At the governmental level, Southeast European countries need to advance national climate mitigation plans and disaster risk reduction strategies that can create an environment for sustainable investment in the agricultural sector.

Scientists have higher confidence about how we can limit future climate change

To effectively advise on limiting human-induced climate change, scientists are assessing radiative forcing – essentially, how much the Earth is heating up as a consequence of more energy radiating down than radiating back out to space. In the new report, scientists have more narrowly determined the increase in global mean surface air temperature that will follow from doubling the quantity of atmospheric CO2 – 3°C with a likely range of 2.5°C to 4°C, compared to 1.5°C to 4.5°C in AR5.

There is a near-linear relationship between cumulative CO2 emissions and the increase in global surface temperature. Thus, limiting human-induced global warming to a specified level requires minimizing cumulative CO2 emissions, reaching at least net zero CO2 emissions. Furthermore, strong, rapid and sustained reductions in CH4 emissions would also limit the warming effect resulting from declining aerosol pollution and would improve air quality.

Under the five new scenarios defined in the report, low GHG emissions scenarios lead within years to visible effects on GHG and aerosol concentrations, as well as air quality, compared to high GHG emissions scenarios, which will result in much smaller changes.

The report further points out that anthropogenic carbon dioxide removal (CDR) has a high chance of removing CO2 from the atmosphere, durably storing it in reservoirs. CDR would compensate for residual emissions to reach net zero CO2 or GHG emissions. If overall anthropogenic removals exceeded anthropogenic emissions and the resulting global net negative CO2 emissions were sustained, surface temperature increase would be gradually reversed.

Even so, other climate changes would continue on their trend for decades, even millennia. For example, even with large net negative CO2 emissions, it will take several centuries to millennia to reverse global mean sea levels. This is one consequence of having acted too slow to limit climate change – and hopefully a wake up call to business leaders, governments, and investors to address the climate crisis today.