Search for...

Starting a company and raising funds from venture capital is like entering into a long-term relationship for all stakeholders involved – founders, employees, and investors. Successful ideas need their time to gestate, which from an investment perspective also means accepting illiquidity in exchange for (hopefully) attractive returns. However, as in every relationship, the ride may have its bumps and the notion of being stuck together “till exit do us apart” may create friction. Since the current average time for a start-up from inception until an IPO (initial public offering of private companies on public markets) is well over ten years, the waiting time for an exit event may seem longer than what some may consider reasonable.

Luckily, there is a solution for shareholders in private companies who seek liquidity prior to an exit event. This solution is the sale of shares to secondary investors. The transactions involving shares of private companies are called direct secondary investments. These transactions are increasingly common also for high-growth, venture-funded technology companies.

Secondary market activity is closely linked to the maturity of an investment universe. Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) with its vibrant yet relatively young tech ecosystem is the next frontier for direct secondary investments.

Between 2003 and 2021, private market fundraising worldwide increased more than twelvefold from around USD 96 billion to approximately USD 1.2 trillion. In 2021, VC and growth equity comprised nearly half (47%) of private equity fundraising. All this VC activity has driven a meteoric rise in the number of funding rounds in later-stage companies and correspondingly of companies hitting a unicorn or a decacorn status. The US alone minted 340 unicorns in 2021, more than in the previous five years combined. As a result, more and more wealth accumulates in private companies.

The unprecedented growth of venture capital investment has been visible in Europe, as well. In 2021, capital invested in technology companies in Europe peaked at over USD 120 billion, three times more than the previous year and four and a half times more than in 2017. There are now more than 350 venture capital funds active in Europe.

A very interesting case showing the rapid growth of tech ecosystems in specific regions is Israel. More than two decades ago, the country made a concerted effort to focus on the knowledge economy and technology. A boom in early-stage VC funds and accelerators followed and as more investment players joined, more start-ups took off. Today, the Israeli tech ecosystem draws up to 28 times more venture capital per capita vs the US and ranks third globally by the number of start-ups. In 2021 alone, investors committed USD 26 billion to the Israeli ecosystem, a leap of nearly 150% vs 2020, which fuelled 75 IPOs and the minting of over 40 new unicorns.

Yet Israel, while probably the most prominent of the regional ecosystems, is not alone. CEE is showing similar patterns of development as Israel, albeit a decade later. The first pockets of success gave birth to regional hubs, like the success of Skype fuelled start-up activity in the Baltics. Today the region, while still underserved compared to its western counterparts (or Israel), is a thriving market for technology investors. In 2021, venture capital investment into CEE was on track to reach USD 5.4 billion, a 2.3x increase vs 2019.

Yet amassed wealth in private tech companies also creates pressures on their shareholdings. Venture capital funds are usually structured as funds with a fixed lifetime (commonly as 4-5 years of the investment period, followed by 4-5 years of realisation period). At the end of the life of the fund VCs need to return the capital to their investors, limited partners. Yet while the lives of VC funds remained more or less the same over the past decades, the investment horizons of private companies have extended significantly.

In 1999, companies were going public after an average of four and a half years since founding, yet by 2020 the figure had almost tripled to more than twelve years. This extended time horizon to exit means that the investments are staying illiquid for longer, which can put pressure on VCs whose funds are approaching the end of their lifetime. There is a low chance for any reversal of this trend with the recent macroeconomic challenges and uncertainty, as well as a fall in global tech valuations and increased volatility of public markets. By Q3 2022, global IPO volumes and their proceeds fell year-on-year by 44% and 57%, respectively.

One of the solutions, as alluded to already, are direct secondary investments.

Unlike primary investments, where a company issues new shares, secondary investments are transactions in shares held by company shareholders. Such transactions thus present an opportunity for the shareholders of private companies to get (some) liquidity for their otherwise illiquid instruments. Anyone can be a seller in direct secondary investments – investors but also founders and employees (or ex-employees).

While equity is the most precious currency a company has, and therefore can give to its employees, sometimes there may be a problem with the perception of this value transfer. Employees do not always see or appreciate the value of the shares or options they receive. This is either due to a previous bad experience or because they see them as illiquid instruments locked in the company and any pay-out decision is not depending on them.

“We have heard from several founders that it pains them to see how little value employees may assign to their option awards. Founders think they are giving up a rare piece of value, especially if they are after a gruelling fundraising process with investors, only to face not-so-enthusiastic reactions from employees who receive those option awards,” said Lukas Harustiak for The Recursive.

Secondary transactions can help to bridge the value perception gap. Companies can set up, and secondary funds can fund, employee share buy-back schemes that offer employees to partially monetise their vested options. Such programs, which bring home the idea of real (and realisable) value of these options, can then become a potent retention and incentivisation tool for the company in competition for top talent.

“The funny thing is that the major effect of such employee share buy-back programs can be purely psychological. Sometimes it is enough for employees to have just the option to sell to see and understand the value of their holdings and they may never actually use it,” opined Lukas Harustiak.

There may nevertheless also come a time for founders when they need to relieve some of the pressure of building a successful company over a long period of time. Many founders have built businesses of substantial value without financially benefiting from their success. Not to mention the fact that after building a fortune “on paper”, founders’ risk perceptions may be heavily influenced by having literally all their wealth tied up in this one position (as is often the case). Such value concentration may alter founders’ decision-making, not always to the benefit of the company or its investors.

Additionally, founders are also just people with normal human needs. There can be a major disconnect between people’s wealth and their actual financial abilities. It is not uncommon in the start-up world to see paper millionaires who are unable to get a mortgage. One can be only sympathetic to the notion that after years of hard work, successful founders (and their families) would also want to see some of the fruits of their success.

Yet building a successful business may take a lot of time and therefore visibility of exit may be very uncertain or distant. In such instances founders may be tempted to exit too early, not realising the full value potential of the business. Such situations, while possibly making the founders cash-rich at the exit, may nevertheless be suboptimal outcomes for investors, especially later-stage ones, and their realised returns on investment.

Direct secondary investments allow founders to monetise some of their success without burdening the cash flow of the company. They, therefore, allow for relieving the pressures mentioned above prior to the eventual exit. So ironically, secondary transactions involving founders selling their shares can bring value to the company investors as well. As founders gain some comfort in their personal circumstances they can better focus on growing their businesses and thus also investor returns.

“Of course, what is important in these cases is the balance of the shares sold versus shares retained as investors would always want to see motivated founders whose interests and incentives are aligned with their own,” according to Lukas Harustiak.

One of the common views the companies have of direct secondary investments is that it is a useful tool to manage their cap tables. This means that secondary investors buy selected shareholders of the company. This can be for example used to reduce the size of “dead equity”, which is the part of the cap table occupied by people no longer involved in the business, like former employees.

“Large percentage of dead equity is often seen as undesirable by investors and may cause problems for the company when fundraising. This is especially true if such shareholders have a significant share of votes in the company as their motivations may be unpredictable,” said Lukas Harustiak from Flashpoint Secondary Fund.

Another reason to consider secondary transactions for cap table management is to alleviate shareholder pressure for liquidity. This is related to the already stated issue that the time horizons of VC funds may not match the company’s development and pathway to exit. Shareholders may thus push for exits due to their own fund limitations rather than for reasons which are in the best interest of the company. Such situations may restrict further company development or lead to a premature exit.

Direct secondary investments can be also used to restructure or upgrade the shareholder base for a more institutional profile. This is particularly relevant for companies that grew with capital from “friends & family” but are looking to establish themselves in an institutional investor community. Such companies also tend to have very large cap tables with many small shareholders who are inefficient and cumbersome to manage. Here again, secondary transactions can be handy as companies may use them to rationalise the number of shareholders.

Companies may also find secondary as a helpful financing tool in specific situations such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The acquiring company can pay for the target’s shares either with cash or with its own shares. But acquiring another company using its own shares means also accepting all of the target company shareholders onto the cap table of the acquirer. This may not always be desirable and may end up in a very large cap table. Using cash instead is an option, but start-ups generally raise funding for their development, and M&A transactions are considered an extra spend. In uncertain economic times such as the current one, many companies try to conserve cash since raising new funds is getting more complex and takes longer. Yet, at the same time, the current environment can be the perfect time to think about M&A. Secondaries offer an alternative way to finance such projects, where secondary funds buy out certain shareholders of the target, thus limiting the growth of the cap table or an outlay of cash by the acquirer.

As mentioned, starting a company is like entering into a long-term relationship. Founders would often spend more time with each other than they do with their families. Yet, as married couples can grow apart, so can the founders. The reasons for that are too many to list here, but it is a simple fact of life (and business) that start-ups do go through difficult processes of founder separations. If not managed properly, these situations can kill an otherwise perfectly healthy business. Having a solution in the form of a secondary buy-out of the departing founder can help in the resolution of these issues and thus contribute to the civility and smoothness of the process. This reduces distraction as well as risks for the company.

While the venture capital secondary market has plenty of untapped potentials, it shows signs of rapid growth. At a global level, the market for direct secondary transactions was estimated at around USD 46 billion in 2021, almost doubling from the previous year. This goes to show that secondary transactions are not something exotic and are developing hand in hand with the maturing venture universe.

Indeed, the existence of a secondary market is a sign of a maturing ecosystem. As mentioned, Israel is one of the booming VC markets with a relatively recent history, spanning about two decades. Yet the market has already developed a lively secondary market with several active players in the space. As a result, local VC secondary direct deals have grown in popularity in recent years, becoming available throughout the lifetime of the companies, even from a very early stage.

CEE, which is earlier on the development curve, is a nascent market for direct secondary investments in technology companies. Yet as the development of Israel’s tech ecosystem shows, the size and growth of early-stage primary investments are fuelling the corresponding secondary supply, which is bound to give rise to an active secondary market.

“Direct secondary as an investment strategy is only waking up in the CEE. Flashpoint is one of the pioneers in this space. Yet CEE is really maturing as a venture capital ecosystem and it continues to produce very successful companies conquering the global markets. We see that the region is ripe for secondary,” opined Michael Szalontay.

One could actually say that there is an unprecedented opportunity for secondary investments in the CEE. Unlike in Silicon Valley, there are virtually no super angels in the region who would give substantial capital to companies in the very early stages. As a result, many of the companies grow with capital from “friends & family” and their cap tables can get very large, with large numbers of very small shareholders. Many companies in the region are at a development point when such cap tables should be rationalised or institutionalised. Here is where secondary funds can help.

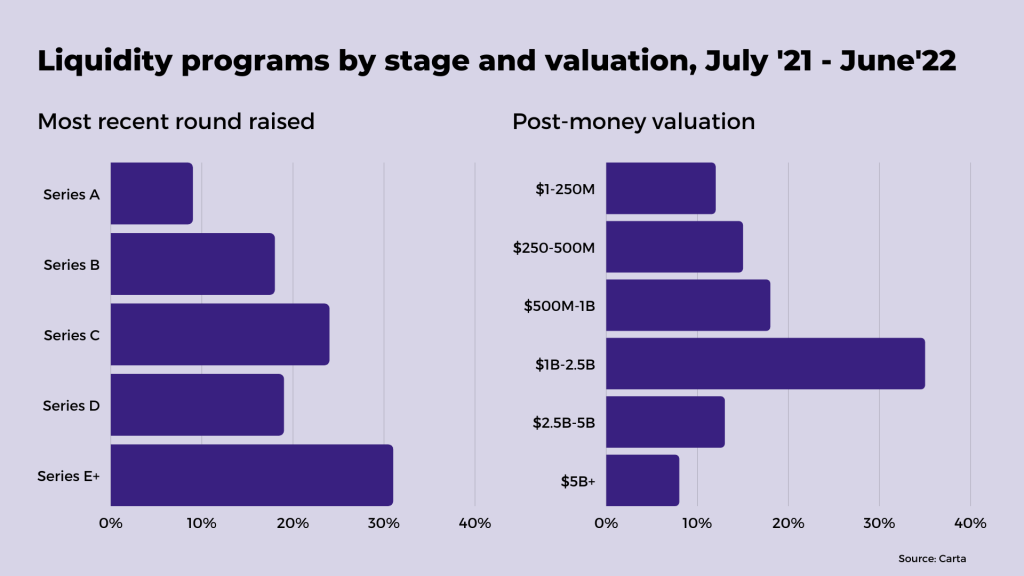

When does it make sense to do a secondary transaction from the start-up perspective? What is the market practice? Many market participants consider it a tool only reserved for really mature companies. Yet this view is in contrast with actual practice. As Carta’s data shows, such transactions are evenly distributed across different sizes and stages of businesses.

Overall around half of the secondary transactions happen before Series D financing, in other words still in a stage far from mature when companies usually still show (and expect to show) major growth and have several years until they start to think about an exit. Interestingly, some recent periods are showing an increased proportion of secondary transactions involving earlier-stage businesses, in Q2 2022 this was 59% for Series C or earlier companies.

Similarly, and contrary to a popular belief, around half of all secondary transactions occur before the companies reach unicorn status. While transaction sizes are naturally bigger for larger companies, with median tickets north of USD 25 million for unicorn companies, growing to USD 85 million for companies valued at USD 5+ billion, the stakes transacted are usually quite small at around 1%. In contrast, the median stakes transacted for companies valued at less than a billion is 3-4%.

Furthermore, transactions are distributed across diverse industries, from SaaS to Fintech, Internet & Media, Healthcare, and Hardware. This means secondary transactions are not a phenomenon isolated to a particular industry or a company in a particular stage of development. They are a tool increasingly used by companies, founders, and investors and they are much more common than many people may think.

Despite the growing commonplace of direct secondary investments, selling shares in private high-growth companies can still be a sensitive topic. One of the reasons is the signalling effect of such transactions. Some may wonder why people would sell if they believe in the future of the company.

“It would be a mistake to automatically assume that selling shares in a company means that something is wrong. As companies raise primary capital for different purposes, so can their shareholders sell shares for various reasons. These can be completely unrelated to the health of the company. Therefore what kind of signal such a transaction sends is closely related to the motivations of the sellers,” according to Lukas Harustiak.

As practice shows, it is perfectly conceivable that even a healthy growing company with shareholders believing in the future of the business will have the very same shareholders wanting to sell a part of their holding. The desire to monetise, at least partially, private positions and thus de-risk one’s investment or dilute wealth concentration is well understandable. Additionally, there are several benefits of secondary transactions for the companies as well. We could therefore expect that secondary transactions in VC-funded tech companies are here to stay and most probably even grow.

“We think founders should see secondaries as an additional tool in their toolbox. And they will need all the tools possible to build successful businesses. There are horses for courses and secondary investors can address specific types of issues that traditional VCs whose DNA is in primary transactions won’t. A cap table limited in size is advisable, yet it should be diverse enough, including secondary funds, to keep the overall flexibility to cover various types of transactions,” said Lukas Harustiak for Recursive.

The traditional business management notion is that managers cannot change anything they want about the company they manage, but its shareholders. Due to the existence of secondary funds, this is no longer true. Anything can be changed.