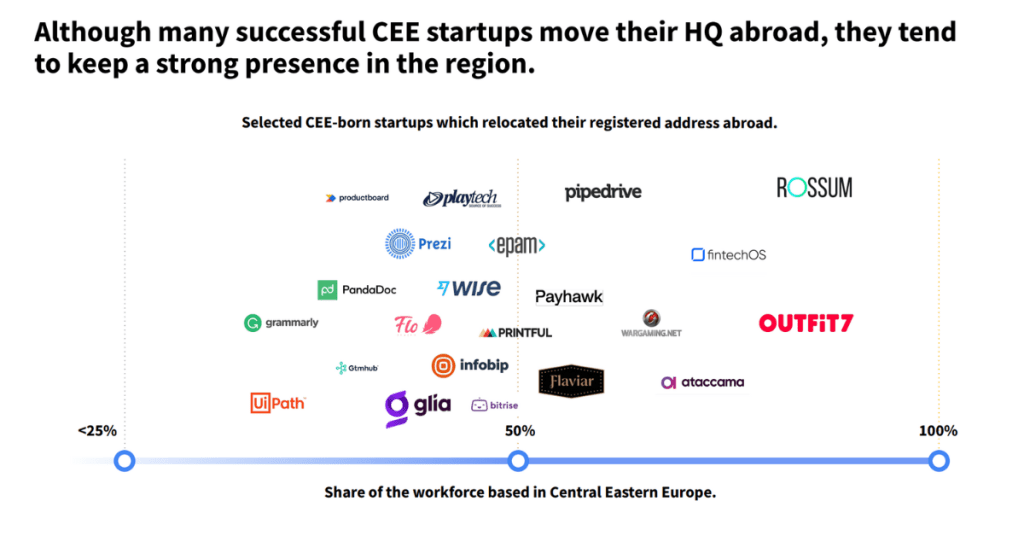

Almost one-fifth of the startups born in Central Eastern Europe (CEE) which have raised more than €1M, move their headquarters abroad to top scaling destinations such as the US West and East coast and the UK. Examples include the first unicorns of Croatia and Bulgaria – Infobip and Payhawk, which are both headquartered in London, the Romanian-born unicorn UiPath which moved its HQ to New York, and the Greek soonicorn Blueground which also “migrated” to the US. Why startups relocate is a multi-faceted story that we will seek to tell today.

Enticed by the opportunity to gain access to more capital, larger ticket sizes, and international talent in order to successfully enter new markets, many regional founders decide to continue writing their success stories outside CEE. In numbers, this means that around $50B in enterprise value has flown out of the region.

“Moving our headquarters to a Western market came with a lot of advantages, including access to a large base of new customers, better positioning in front of enterprise customers, access to investors, diversification of business risk, and higher competition which makes the product better. The process, however, has been a challenge, due to many factors. The first barriers we encountered were connected to the legal and financial aspects. Being headquartered in a Western market implies having more expensive resources and many direct competitors,” Andreea Plesea, co-founder and Global VP of the Romanian-born conversational AI platform DRUID AI tells The Recursive.

Why startups relocate: investments, talent, legal requirements. Is there something else to the story?

“The basis of the decision to move the HQ is access to capital. The geographical focus of VCs plays a role in that, so there is a need to differentiate between those VCs which are active in regional areas (SEE/CEE/Europe or USA or Nordics) and those that invest globally. Regional VCs who are most often the first investors in CEE-born startups, do not impose the relocation. If they are happy with the go-to-market strategy of the team, they invest without any other terms. The global VCs and those whose geographical focus is outside the CEE (such as in the US, Asia, or Western Europe) usually have a saying in the relocation decision,” Cristina Toncu, Cofounder and Managing Partner of Techcelerator.ro and Regional Growth Senior Advisor of ROTSA (Romanian Tech Startups Association) explains, adding that most of the times, the new investment partners ‘suggest’ to the founder to make this move.

According to her, this is related to both the legal and market specificities of VC investing. In order to lead an investment round, the investors must pass a procedure to invest in a startup in their jurisdiction. While on the market side, the investment is set up based on some clear OKRs imposed on the founders for short-medium and long-term growth, which most of the time could be achieved in larger markets.

Momchil Vassilev, Managing Director of Endeavor Bulgaria, doesn’t fully agree that it is a matter of geographical focus. “This might have been an issue 5 years ago, but it is certainly not anymore. Judging from our experience with Endeavor Catalyst working with some of the best global VCs such as Sequoia Capital, having a geographical focus is no longer a common practice. Gone are the days when Silicon Valley VCs would only invest in founders at a Uber distance,” he jokes.

Investors call the shots

“Attracting international investors is a necessary step in the evolution of a startup. Even though an increased number of funds have been raised regionally in the last couple of years, there are still not enough growth equity VCs. Most often international investors are not well-acquainted with the regional market, so they are more willing to invest in founders who have already been backed by regional VCs. This de-risks their investment. When it comes to the stability of our legal frameworks, however, international investors don’t usually feel very comfortable with them. This naturally makes them encourage founders to move headquarters to a country with a more stable framework,” Momchil Vassilev highlights.

As it turns out, from the perspective of international investors, asking CEE founders to move headquarters is more of a practical matter as they would prefer having their portfolio investments clustered in one familiar jurisdiction.

In theory, if the CEE creates a strong regional brand as an ecosystem with a stable legal framework for doing business, Western investors would not have anything against investing in a regionally-headquartered startup. But in practice, there are many legislative and judicial changes to be done before governments reach the stability of Western markets.

As Andreea Plesea explains, moving the headquarters from Romania to the USA was the next step for the growth of DRUID AI. “Having the HQ in a larger and more competitive market is crucial in the scale-up phase that we are in. With this action, we will gain more exposure and will become more visible to large enterprise companies. Also, this means faster time to market, a constant updating of the product, and healthy competition,” she adds.

Can’t the same objectives be achieved by opening a new office, instead of changing the HQ altogether?

“From a founder’s point of view, moving is important in order to find a good local team, especially for a B2B product. This means that there is no need to move the HQ, a local office is enough. From the investor perspective, the HQ matters. In Asia for example, you could not raise a round having your HQ in Bucharest,” Cristina Toncu comments.

Does the CEE miss out on the upside of success?

While scaleups get access to the capital and clients of larger Western markets, some investors and policymakers believe this means that CEE misses out on the upside of their success.

The decision to move the HQ has immediate economic implications on the country of origin or the region itself. These implications are mostly negative and connected to losses in revenues, taxes, new jobs, market growth, technology, and even prestige.

“However, this phenomenon also brings some benefits to the home market, even if it takes some time before these benefits are realized. Founders exit and give back their contribution to the local ecosystem, as mentors backing up accelerators, as business angels, or as setting up VC firms. Take, for example, UiPath which moved to the US, grew up to a unicorn, made IPO, and “returned” a bunch of experts who now help the local ecosystem one way or another by joining new startups teams, building their own products or joining VCs” Cristina Toncu highlights.

According to Momchil Vassilev, it is not about the change of headquarters itself, but rather how founders design the process. He refers to UiPath and Payhawk to exemplify the difference. “If founders decide to move their management abroad and leave only operational talent at home, this would have a negative impact on the local ecosystem in terms of a talent drain and impede the development of the ecosystem as a whole. On the other hand, if founders decide to leave the core team at home, and hire talent for missing senior positions abroad, this would bring more expertise in the local ecosystem,” he says.

In order for founders to be able to attract top talent regionally, there are again certain legal prerequisites that need to be met. Regional governments must create the right conditions for companies to bring top talent from abroad by enriching the national legal frameworks with initiatives and procedures such as blue cards and startup visas.

“What is even more paramount, is for the founders themselves to remain engaged in their local ecosystems and to invest back into the growth of fellow entrepreneurs. In order for the regional innovation landscape to reach the next stage, every country should have around 5-7 successful founders who have turned ecosystem heroes by creating whole innovation bubbles around them,” Momchil Vassilev comments.

Does “Made in the USA” sell better?

It’s a common saying that the “made in the USA” label accelerates the buying process for any tech company, especially in the B2B industry. Is that really the case in 2022, going into 2023 now? And does this trend play a role in the decision of CEE founders to move their headquarters?

“I have mixed feelings about it. Five years ago when we started Techcelerator, the Romanian startup community was very frail. And going out into other ecosystems for conferences or other partnerships I would have admitted that we were lacking attractiveness. Today, however, the top technology startups are very much comparable with the best ones in the west of Europe. We’ve got some success stories and this fades away the blur in the eyes of the most established investors about the SEE and CEE region. The region gave the world some unicorns, like UiPath (Romania), AirSlate (Ukraine), Payhawk (Bulgaria), or Glia (Estonia), and that grew the investor’s appetite. We have new emerging hubs, like Liubliana, Belgrade, or Sofia where the number of startups and VC investments grew x15, even x20 times in the last year,” Cristina Toncu says.

According to Momchil Vassilev, it no longer makes a difference for clients whether the product they buy is made in Bulgaria, the UK, or Bangladesh. He points out that among the network of Endeavor Bulgaria there are companies that sell software to the US Pentagon, NASA, and international airports.

Empowering CEE founders to create global success locally

“It’s all about boosting the ecosystem around them – enabling their growth by offering them all the necessary tools and the freedom to do it, here, without the need to relocate elsewhere,” Cristina says.

According to her, the decision where to be located as a scaling company is not always a matter of money. Founders need and want to be surrounded by market players who will enable them to grow faster and more sustainably, including partners, investors, experts, and clients.

“It’s our responsibility to create the right legal conditions for scaling founders to continue writing their success stories locally. This means building a business framework that reverses the brain drain and assures international investors that there are no legal risks or uncertainties in supporting regionally-headquartered startups,” Momchil Vassilev concludes.