As the corporate decarbonization commitments increase, so does the confusion about what these claims represent. More and more companies proactively and voluntarily step forward to address the challenge of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The trend is certainly in line with many stakeholders’ expectations, as well as international commitments to limit global warming, such as the Paris Agreement.

But how often are these claims in line with companies’ true impact, as defined by reporting standards and verified with data?

“You cannot change anything that you have not measured, because you do not have enough evidence to make a decision on how to act on it,” Lubomila Jordanova, founder of Plan A, told The Recursive. Plan A is a Berlin-based company with a carbon accounting software solution that enables businesses to monitor and reduce emissions.

Yet companies, especially small ones, are confronted with various limitations. To start with, there is a lack of consensus in the terminology used to describe decarbonization pledges, from carbon-neutral to carbon positive, carbon negative, and net-zero emissions. For instance, the Carbon Neutral Protocol definition says that net greenhouse gas emissions from the entity, product, or activity need to be zero for a defined duration of time – hence not forever. The conversation gets even trickier when determining what GHG emissions to measure.

In this article, The Recursive’s analysis indicates that:

- Companies should be using scientific data and standards to report and commit to GHG emissions reduction, thus avoiding greenwashing;

- Decarbonization is a process – companies can work with reduction and offsetting strategies along the journey;

- There are new opportunities in the EU, supporting decarbonization, innovation.

How to avoid greenwashing

When making carbon neutrality claims, a good rule of thumb for companies is to state what scope is covered in the claim. Lubomila Jordanova guided us towards the different types of emissions.

Under the Greenhouse Gas Protocol international framework for calculating emissions, these are categorized into three scopes.

- Scope 1 includes emissions, generated from the company’s own operations. These are sources owned and controlled by the firm.

- Scope 2 refers to the services purchased by the company in the form of electricity, cooling, and heating.

- Scope 3 includes the emissions created in the supply chain.

The classification varies with each industry, depending on its operating model. For instance, in the case of a software tech company, emissions generated by its servers would fall under scope 1.

Guidance on scope 2 and scope 3 emissions adds new levels of transparency and accountability to corporate reporting standards. Energy generation is responsible for nearly 40% of global GHG emissions, with half accounted for by industrial and commercial sectors, making scope 2 guidelines essential. Meanwhile, the scope 3 standards allow companies to assess the impact of their entire value chain, an often missed opportunity to understand a company’s overall footprint.

“This is the only correct way in which you can calculate your emissions, anything else is not exhaustive of what your environmental footprint represents,” Lubomila adds.

Companies normally start with scope 1 and 2, for which data is easier to find. In terms of scope 2, companies then look at emissions from their employees’ commutes, says Lubomila. The discussion gets trickier when we start talking about suppliers. In an exercise of screening the websites of companies making green claims, the European Commission determined that in more than half of cases traders did not provide easily accessible evidence to the claim.

“One problem lies with the fact that companies do not follow science when they calculate their emissions. And also, they are not using accurate data to calculate the emissions; they are using predominantly averages because they cannot access the data,” Lubomila explains .

Another key reason voluntary commitments have sown so much confusion is the absence of a regulatory framework for the full scope of emissions, she adds. This is a missed opportunity to incentivize the correct portrayal of decarbonization efforts.

Starting 2022, however, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive by the European Commission will oblige firms with more than 250 employees to report the full spectrum of emissions. That being said, smaller companies will still lack regulatory obligations and may still fall into the trap of communicating inflated claims to position more favorably towards stakeholders.

“Our advice, especially to smaller companies, is that they make sure they commit to things that they know they can achieve, and also to things that are small steps out of a big journey. Sustainability is a process. It’s not something that happens overnight,” Lubomila adds.

Tackling decarbonization one step at a time

“There are concrete things you can do without having to make bombastic claims of carbon neutrality goals that maybe cannot withhold the test of time,” Lubomila exemplifies.

One way to decarbonize business operations is to take a series of carbon reduction measures in-house. This implies decreasing emissions from the company’s activities and products. And if we talk about big tech companies, this strategy seems like the one to go. For example, as part of their commitment to becoming carbon negative for all 3 scopes by 2030, Microsoft announced they will cut more than half of current emissions. They then split down the targets and steps to be taken for each emission scope.

For Microsoft, carbon neutrality is not an ambitious enough goal. That is why aside from focusing on emissions prevention, they are investing in the removal of existing carbon. To that end, the company will be investing $1 billion in a Climate Innovation Fund to accelerate the development of carbon reduction tech.

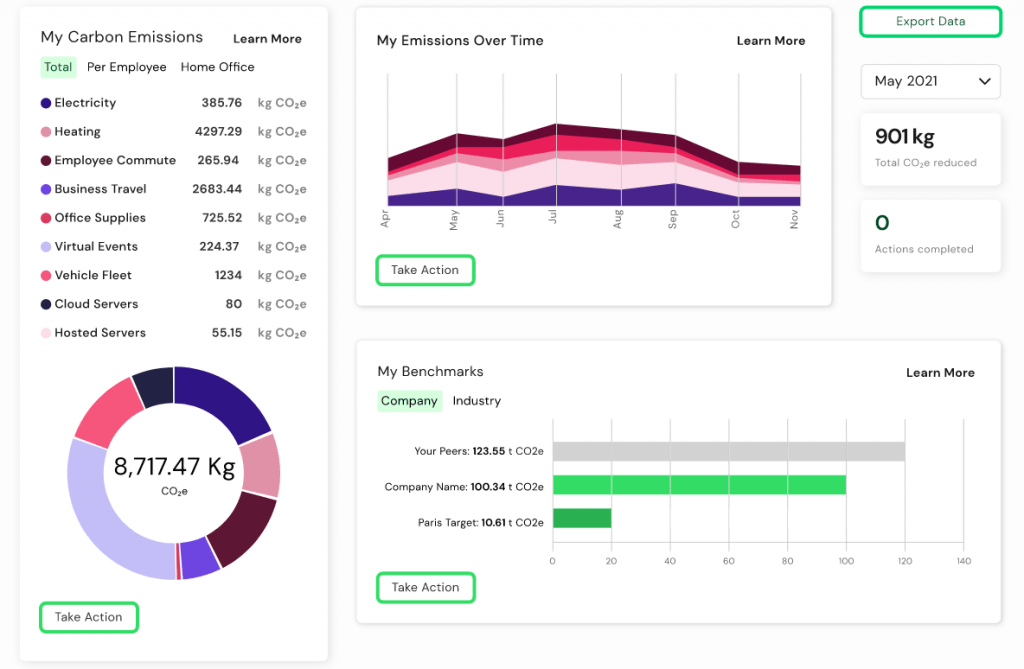

To begin reducing emissions in-house, companies can work with data-driven solutions for carbon accounting and reduction. Let’s take the example of Plan A. “Our main focus is on getting companies to really organize their sustainability efforts in one platform,” Lubomila says. Their carbon accounting software essentially helps companies calculate emissions, visualize data, and identify the optimal ways to reduce carbon impact throughout the firm’s operations. This includes connecting companies with different strategies for decarbonization, from carbon removal, sustainable investments, renewable energy transitions, to social impact projects and carbon offsetting.

An example of a company that worked with Plan A is Gifted. The application allows people to extend the life cycle of a product, by offering it as a gift. The team has worked with Plan A to set the company in a sustainable way from the beginning. Gifted set up the software and processes needed to minimize emissions generation in-house. This affected decisions about the office and the hosting servers.

If it is not feasible to make such an investment right away, breaking the plan into smaller, manageable parts can make implementation and results tracking more feasible. There are also tons of free educational resources online that can assist companies in the transition. “Maybe your first focus on office sustainability and only later on at a policy level of sustainability, where the way you educate your employees about the growth of your company also embeds this mindset,” Lubomila adds.

Another strategy companies base their decarbonization plans on is to offset carbon emissions by purchasing carbon credits. These are meant to compensate for the CO2 emissions, produced by companies in various ways. Carbon credits are measurable and verified emission reductions from certified climate mitigation programs.

Such projects include replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources, investing in growing forests that sequester carbon and developing technologies that can capture and store it in a less harmful state. Carbon offsetting has a place in the transition. In certain instances, changing the business operating model cannot be fast or safe enough for the company to work on its own. That being said, offsetting will not be an ideal solution in the long term.

Lubomila gives the example of a tech startup that starts getting financial support. As the team and operations scale, the company’s impact also increases. Offsetting emissions instead of reducing emissions in-house will not account for these rapid changes in the company’s growth. CO2 emissions will still rise and more efforts will be needed on the side of companies and technologies that offset emissions.

Exciting opportunities for decarbonisation

“What is lacking in the market is definitely funding, especially in Central and Eastern Europe”, Lubomila says. Part of the reason is that investors have not fully grasped the potential of investing in technologies such as hardware that play a role in the sustainability space. Such projects come with different life cycles and value propositions. “We are building a new economy, an economy that is more sustainable, that is focused on different KPIs than the one that we have now,” she adds.

Luckily, some new initiatives are looking to address the issue of funding. In the construction sector, a global open challenge recently opened up. The Innovandi program partners up tech start-ups and companies within the Global Cement and Concrete Association to accelerate innovations that can drive decarbonisation in the sector. They are looking for startups that work to reduce or avoid carbon dioxide emissions throughout the concrete value chain. The areas of interest include carbon use in the construction supply chain, calcination technologies, and carbon capture innovations.

In Europe, a new partnership between the European Commission and Breakthrough Energy, founded by Bill Gates, will mobilise an investment of €820 million between 2022-2026 in climate-smart technology projects. The program targets start-ups in fields such as green hydrogen and direct air capture that are currently too expensive and uncompetitive to get scaled.

Hopefully, this will also signal the value in the market to other regional stakeholders, such as venture capital funds. “There is a lot of innovation in space. But this innovation somehow ends up quite often corner, because there is not enough understanding and maturity in the market about why this is something that needs to be implemented now at a larger scale. Fortunately, we have quite a lot of indicators that this is going to happen. Let’s see if the speed is the correct one,” Lubomila concludes.